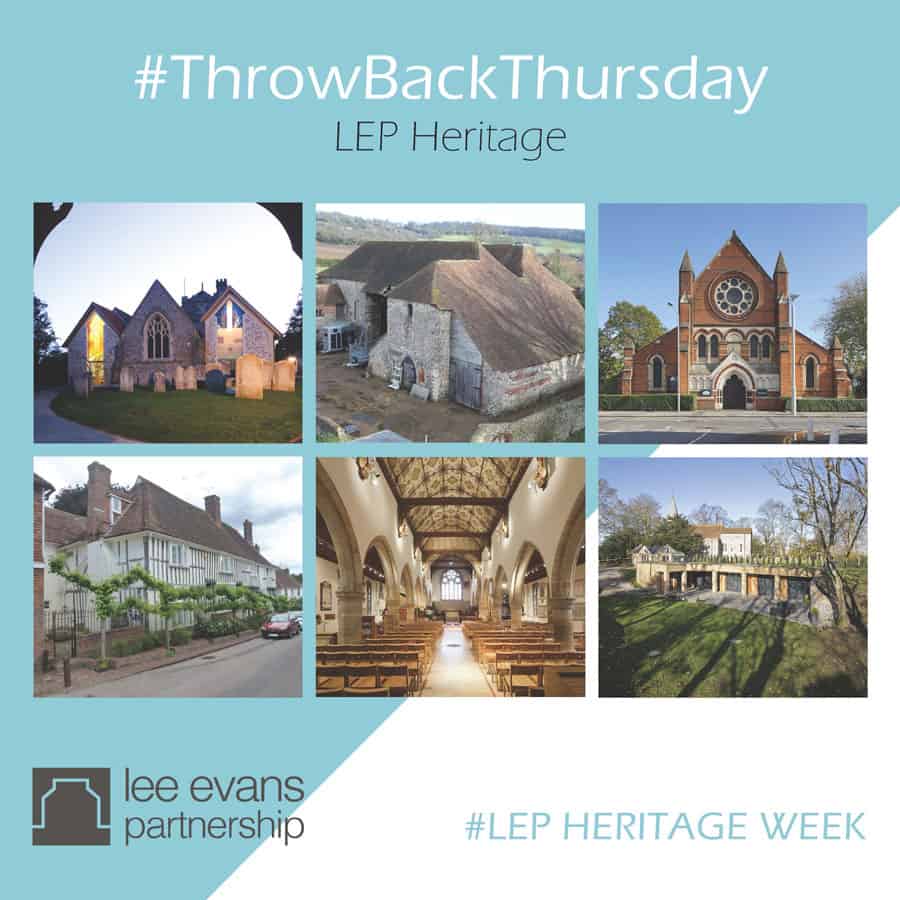

HERITAGE WEEK – #ThrowBack Thursday

On our penultimate day of #Heritage Week there was only really one place we could go… #ThrowBackThursday!

On Day 4 we are bringing back some of our Team’s favourite schemes from the last 10 years, which display the diversity of projects our Conservation and Heritage specialists work on.

St Margaret’s Church, Angmering, W. Sussex

Back in 2009, LEP completed a somewhat controversial extension and reordering scheme at St Margaret’s Church in the pretty Sussex village of Angmering.

One of the largest evangelical churches in the Chichester Diocese, Grade II* Listed St Margaret’s can be dated back to medieval times, with subsequent development during the 15th century. In the 1850s, famous Victorian architect Samuel Sanders Tuelon carried out a major reordering and extension project at the church. The church has an impressive architectural heritage, however the rector, the Revd Canon Mark Standen, feared it could impede on their future liturgy and mission.

As a forward-looking church, the key issue identified was the unwelcoming entrance, which was neither visible from the village or by passers-by. Additionally, restrictive and uncomfortable pews with poor sight-lines, a lack of ancillary facilities, and impractical, underused areas were additional concerns.

Listening carefully to the church’s concerns and requirements, LEP’s main architectural objective was to create a building which would be seen as an inviting beacon in the community. Our solution was to create two new modern gabled extensions on the visible eastern façade, relocating the main entrance there. Uncomplicated, direct and completely contemporary, the new extensions were inspired by Tuelon’s original design, which projected a three-gabled rear elevation towards the village.

New eastern facade – daytime

We worked closely with expert stonemasons Hoopers of Middlex to create the new flint and stone extensions, ensuring a common narrative of materials between old and new, were created. Modern bespoke glasswork designed by Chichester artist Mel Howse was installed – a rear opportunity to introduce such into an important listed medieval and Victorian church. Etched and enamelled, the impressive glazing provides a powerful sense of presence and welcomes visitors, who can catch glimpses of life and movement within the church.

New bespoke glazing by artist Mel Howse

Internally, extensive reordering has taken place, creating a spacious, uncluttered interior which allows the church flexibility for both liturgical and secular uses. The historic Tuelon lectern and font have been repositioned, and the pulpit removed, replaced by a mobile lectern. Choir stalls and the majority of pews were removed (with two retained for posterity), replaced by high quality chairs which can be easily reconfigured. A new sunken baptistry and raised oak floor with underfloor heating have been installed.

Reordered church, and sunked baptistry

The new extensions also provided the church with the opportunity to install ancillary accommodation, including a kitchen, WCs, office and meeting spaces, and ample storage.

The church family now have a flexible and welcoming building from which to continue their mission into the future, and LEP were delighted to be part of the Church’s impressive architectural history.

Archbishop’s Palace, Charing

In 2016 we had the pleasure of being invited to carry out stabilisation work to the Grade 1 Listed, Scheduled Ancient Monument, The Archbishops Palace, in Charing, Kent.

It is believed that the Archbishopric of Canterbury owned 17 palaces during the medieval period. These were high status domestic residences, providing luxury accommodation. It was not unusual to have these buildings within an enclosure or a range of buildings, as can be seen at Charing, and to reflect the high status of the site the buildings were typically built from Kent Ragstone.

This site is believed to have first been used in the 8th Century when the land was presented to Christchurch Priory, and afterwards records show the evolution of the site with buildings being constructed by various preceding archbishops. Whilst the condition of the buildings today varies, with some of the buildings nearing a ruinous state, there are others which are inhabited. Despite the varying conditions and the evolution of the site, the layout of the original complex is still apparent, and historic records provide further details of the original function of each structure.

The precinct boundary wall survives, indicating the full extent of the Palace precinct, whilst the lack of alterations to the interior of the site and its layout has enabled the survival of upstanding and buried archaeological remains relating to the occupation and use of the site. It is this lack of historic alterations which provides the site with a sense of increased significance, as it allows the site to be read quite clearly. Most of the buildings which form the quadrangle, including the Great Hall, chapel, gatehouse, west range, the farm house and precinct boundary wall, date from the 14th Century, and the complex is still entered through the stone arched gatehouse. To the east of the quadrangle is what was once the Great Hall, thought to have been built between 1333-1348. The land remained under the control of the priory until 1545 when it was acquired by Henry VIII through an exchange with Cranmer.

Part of the wider complex showing the farmhouse (left) and the Great Hall (behind, right)

The Great Hall is thought to have been converted into a barn around c1725-30, although there is some conjecture about the date of the current roof. This building would have had a hammer beam truss spanning east to west, allowing for a gable on the north wall, which would have had a window set within it, and part of the cill for this is still present in the wall.

Severe structural issues requiring stabilisation

The north wall of The Great Hall had been slowly leaning over in recent decades and after a temporary fix during some decades ago the wall was continuing to rotate. The need for emergency repairs was highlighted, and a grant from Historic England was obtained to stabilise the structure. Working with specialist conservation engineers and contractors Astral Ltd., we undertook investigation work to understand the complex issues which were present in the site and building and devised a multi-faceted solution to stabilise the building preserving it for future generations.

Stabilisation works in progress by Astral Ltd.

Christ Church Surbiton

Christ Church Surbiton is well loved and intensively used, and seems from the outside a very typical mid-Victorian London city – or rather suburban – church. Inside, though, there is much that is very special – and even more so now that it has had a £1.2m re-ordering, all orchestrated by LEP.

The material that we had to work with was already good. A really stunning roof and a fine Burne-Jones window to start us off, to say nothing of the glorious polychrome brickwork. The project is just a first phase and resolves all the accessibility problems and brightened and enhanced the many superb existing features.

Beautifully decorated ceiling at Christ Church Surbiton

As we so often find, however, our Victorian forebears can sometimes leave a legacy of curious building practices and the project has addressed some surprising structural issues too.

We engaged Claremont Construction, a local firm, whose workmanship has been second-to-none, and the quality speaks for itself. A major change was the removal of the very tawdry 1970’s partitions and north-facing dais and a further ill-conceived partition was removed – revealing the excellent Sanctuary tiling – and new first floors and staircases make much better use of the building’s envelope. We’ve put in a new tiled floor with underfloor heating and an immersion Baptistery with mosaic and a skillfully crafted oak cover, with a brilliantly simple heating (electric wand) and emptying systems (just put your foot on the pop-up waste!).

Reordered church

The church now has a state-of-the-art audio-visual system and LED lighting, and a simple but striking change was the matter of stripping the paint from the Mansfield Stone columns, which enriched the colour palette, especially when set off against the sparkling new tiles and the Keim mineral paint that now decorates the lower walls.

A finishing touch is the bold new window which illuminates one of the new meeting rooms. A modern intervention which, we feel, enhances and enlivens the historic fabric.

Cumberland House, Chilham

Cumberland House forms part of a very prominent Historic streetscape in the well-known village of Chilham. The long range of timber framed buildings had been given an award-winning make-over several years previously but unfortunately the choice of materials had been poor and the house was showing signs of rapidly advancing decay.

LEP was invited to investigate the issues, the most immediate one being that “there are draughts coming right through the walls!” What became quickly apparent was that there were ominous gaps and signs of movement at the interface between the rendered panels and the timber framing surrounding them. Certain timbers also showed significant evidence of recent decay as well, and clearly the issues were connected.

It transpired that many of the rendered panels had been replaced by, or coated with, a very hard and in-flexible cement-like material which did not move harmoniously with the slight seasonal movement of the oak framing that had been harmlessly going on for around five centuries. Previously, any movement had been taken up by the flexible and self-healing lime that previously formed the infill panels. This rigid and inappropriate modern intervention had very much upset the equilibrium, and was now allowing draughts and water to come through.

Failing cement render before removal

Cement render being removed

The sheer scale of the problem – and likely expense – was initially daunting. However, something had to be done. First of all, we explored the possibility of keeping the cement panels and forming a breathable and flexible interface between the cement and the oak. Not by any means ideal or best practice, but a large sum had not long before been invested in the building’s refurbishment and we felt that we should explore this option upon some degree of a scientific basis. We quickly realised, however, that there was only one viable long-term solution – the removal of the cement and repair whatever remained beneath of the earlier material.

Kent Conservation and Restoration Ltd of Harrietsham were appointed to carry out the work, with the project running seamlessly, on budget and within a very reasonable timescale.

Listed Building Consent was required for the work which was carried out in phases under the watchful eye of the Area Conservation Officer. Thankfully, far more of the historic material was salvageable than we had ever imagined viable. The cement had been applied quite thickly over historic substrates that varied but generally involved riven chestnut or oak laths and, on several occasions true wattle and daub, sometimes containing vegetation and animal or bird nesting material that had not been disturbed for centuries. Sometimes the cement had been applied directly on the old lime render. In most cases, the cement just came away- sometimes in very large and heavy sheets, with the matrix of laths embossed into the back.

The removal of the cement revealed a series of different repair scenarios and challenges. In many cases a three coat fat lime plaster was simply applied to what lay beneath, but in other cases we put in new riven chestnut laths and let in new sections of timber, with resin or tradition peg jointing techniques. The oak used was all re-used old timber from the builder’s own stockpile – close enough of a similarity to make the repairs outwardly seamless, but still different enough to enable the story to be told if you look closely.

The final decoration was with breathable Earthborn clay paint and the building seemed to glow. Draught-free, flexible and hopefully keeping decay at bay for many years to come.

Holy Trinity Church, Cuckfield

Located in the village of Cuckfield, Sussex, Holy Trinity Church underwent a significant internal reordering and restoration project orchestrated by LEP back in 2013. As part of the works, the Grade I listed building, originally founded in the 11th Century, underwent several highly contested changes to enable the church to better fulfil its mission.

Countless reorderings had taken place at the Church over its 1000-year history, allowing it to adapt to the changing needs of the mission and worship. Victorian restoration works, by architects George Frederick Bodley and Charles Eamer Kempe, moved the pews, altered aisles and dramatically changed the chancel, making for a striking building and their work now holds a great deal of historical importance.

30 years later, Bodley returned and installed a chancel screen, separating the nave and main chancel area. Although this created beautiful sacred spaces, from a design perspective it had the unfortunate effect of hindering the church’s mission. It was also expressly against the wishes of the vicar to whom it was a memorial!

LEP’s project brief was to create a more comfortable church with improved heating and audio-visual aids. The Church felt that the existing pews, chancel screen and flooring were no longer suited to their congregation’s needs, and even considered that they were potentially damaging to their mission.

We proposed several drastic changes to correct these issues. It was important that we took our time to thoroughly understanding the building’s past, its history and its significance. We believe that only by gaining an appreciation of the significance of the building fabric can we then seek to look for opportunities the building presents. In the case of Holy Trinity Church, it was found that Bodley’s chancel screen was not part of the original reordering, being a later addition, which gave the authorities comfort to accept our proposed change.

The design team devised a plan to relocate the screen to the tower to form a lobby space, ensuring it remained a physical part of the Church’s history. The relocation, carried out by Seth Evans Joinery, also had the benefit that it was reversible and whilst moving it, the team discovered that the screen was a beautifully constructed kit of parts which easily came apart almost like a piece of Victorian ‘Ikea’ furniture. It fitted perfectly!

Bodley’s screen relocated into the tower entrance

In the Nave, fixed seating was replaced with chairs, making a flexible space which could also be used for secular purposes. The chancel tiling has been fully restored, and a new larger dais installed to better accommodate the choir. A new audio-visual system was fitted with discrete speakers so as not to detract from the buildings’ historic aesthetic.

The crowning feature was the sympathetic repair of the magnificent 1844 Baptistery tiling, by Chamberlain of Worcester, which had deteriorated badly. A large percentage of the intricate patterned encaustic tiles was saved and new replicas made to replace the very poor ones using much care and traditional methods by Robus Ceramics, a local specialist, helping to keep some old skills alive. Interestingly, a large crack can be seen in the baptistery font, held together with an iron strap – supposedly, where one of Cromwell’s horses kicked it over!

Deteriorated encaustic tiles (left), and sympathetic repair (right)

The scheme demonstrates not only the need to make necessary changes to our churches to secure their future, but also the importance of empathising with their historic context. With the growing appeal of the internet and social media, modern generations would rather interact online meaning that cold draughty churches hold little interest to them. Our churches are essential tools for mission and worship within society and the needs of a modern congregation subsequently deserve confident architecture which makes our ordinary parish churches attractive and comfortable spaces for all generations.

“The Wilderness”, West Stourmouth

Completed in 2018, this private residential scheme showcases how our multidisciplinary team at Lee Evans Partnership can work effectively and efficiently together to make our clients’ visions come to life. All of the LEP family had involvement with this project: The design was imaged by our talented architectural and Heritage teams, with advice from our in-house CDM specialists, and successfully steered through a challenging planning process by our knowledgeable planning consultants.

Undergoing construction

‘The Wilderness’, a three-bedroom modern family home, is located in the rural Kent village of West Stourmouth, directly adjacent to the village’s important Grade I Listed All Saints Church. Due to the sensitivity of the area, our design ensures that the property is barely visible from the public highway, due to its partially sunken nature. The property presents to passers-by as a modest and sensitively restored small original school-house, previously associated with the adjacent church. The school-house building – thought to have once been used as the church morgue(!) – has been reimagined as the property’s main entrance, from where a new stairwell drops down to an open-plan single-storey luxury home.

Old school house forming the discrete property’s new entrance

The curved sweep of the building footprint assists in visually minimising the form of the structure, and the incorporation of floor-to-ceiling glazing on the inner curve floods the living areas with natural daylight. Discrete sun pipes and a glazed courtyard provides natural light to the rear rooms. A brick colonnade offers solar shelter in the summer and additional protection from the elements in the winter, and leads to a delightful private external seating area, with views over the natural garden beyond, all hidden from view of the public highway.

‘The Wilderness’, with Grade I Listed church beyond

The grass roof was specifically designed to seamlessly draw the eye across the property when viewing from the adjacent level churchyard, thus further visually obscuring the home.

The rural location of the site and its proximity to the adjacent Grade I Listed church presented challenges for our planning team: development of such sites usually being seen as contrary to local Planning Policy. However, by working closely with our designers, heritage advisors and the Local Authority, our Planning Team successfully sought solutions to successfully secure planning for the site.

The property’s green roof flows seamlessly from the adjacent churchyard

The client’s chosen site location – although challenging in terms of planning – was my no means an accident. Being a ‘born-and-bred’ local resident and an organ restoration expert, the client’s vision for the site was to build a home for his family, as well as a workshop from where he could operate his organ building business – an important yet dying trade – in an area which meant a lot to him personally. The workshop is located to the rear of the site, which is again completely obscured from public view.

With works now complete at ‘The Wilderness’, we wish our clients every success in their new home and business premises.

If you have a historic building that you’d like to discuss with our specialist architectural team, get in touch! Please call 01227 784444 or email architects@lee-evans.co.uk